The white lab coat and plastic eye protection glasses may not have changed in the past two or three decades, but who is wearing them has. The number of women entering science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) careers has increased in recent years, but not enough. What needs to be done to ensure the increasing number of women accessing STEM education translates into more gender balance in the workforce?

by Annette Lucas

Men may continue to dominate science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields, but at Vancouver Island University, the number of women conducting experiments, collecting and analyzing data, and using science and technology to solve real-world problems is on the rise.

In 2016, more women graduated with degrees in STEM than ever before, according to Statistics Canada, and 20% of women who attended a post-secondary program chose a STEM degree, compared to more than 40% of men. VIU can boast double the national average of females enrolled in STEM, increasing from 40% in 2013-14 to 43% in 2017-18.

“We are extremely proud of the fact we have high representation of women in our programs,” says Chemistry Professor Dr. Erik Krogh, who is also Co-Director of VIU’s Applied Environmental Research Laboratories (AERL). “Many of those students have gone on to lead successful careers in chemistry and the sciences.”

The Gap

In 2015, Engineers Canada, a national regulating organization, launched a 30 by 30 commitment to increase the number of newly licenced engineers who are women to 30% by 2030. By 2017, the number had increased to 17%, up from 13% only two years earlier.

VIU Engineering transfer alumna Tori Koelewyn is concerned industry is only hiring female engineers because of quotas. “As a female, I don’t want to be hired because of my gender, I want to be hired because I am the best person for the job,” she explains.

A Women in Scientific Occupations study conducted between 1991 and 2011 found the number of women aged 25 to 34 employed in computer science occupations fell by about 4,000. The study may be almost a decade old, but the trend has continued.

“In two of my courses, out of 24 students I only had two women in each class,” says VIU Computing Science Professor Dr. Sarah Carruthers. Carruthers believes media has created a false image of what computer scientists do. “A common misconception is that computer science is only working with computers or fixing them,” she says. “There is so much room for creativity. As a computer scientist you can be writing software to create art or music or solving social problems.”

The Solution

The sharpest drop in female participation in STEM studies occurs right after high school. The challenge, says Chemistry Professor Dr. Alexandra Weissfloch, is relating the sciences to real life at the high school level for both boys and girls.

“There is a new trend in chemistry called systems thinking – teaching a science in context with other things that are happening around you in the world,” says Weissfloch. “You don’t just learn to balance an equation, you learn to balance an equation about what is happening in the ocean when it is acidified and how it is being acidified, so everything has a context to it.”

Koelewyn says breaking gender stereo- types has to happen at a young age. “You need to educate boys it is healthy to show emotion as much as letting girls know it is perfectly normal to be interested in building with Lego,” she says.

Science, technology, engineering and mathematics jobs are some of the highest paying available, making the question of why more young women are not pursuing these careers even more important. Nearly three-quarters of the top jobs in our country require STEM education and graduates earn 26% more on average. STEM careers encompass a myriad of areas including environmental protection, biomedical device designing, water or food supply improvements, building design, video game development, sanitation and renewable energy to name just a few.

Dr. David Bigelow, Chair of the Mathematics program, says over the past decade the ratio of males to females enrolled in the math minor program has levelled to about half and half. Bigelow says people with math degrees find jobs in tech, artificial intelligence, communications and government.

“Most people have very little idea what real mathematics is about, because it is not really the same thing people experience in high school. Mathematicians are needed to figure out ways to move luggage through airports. Amazon shipping hires mathematicians. Any type of scheduling problem is a mathematical problem.”

Megan Willis, a VIU Bachelor of Science graduate, believes the issue of gender equity in STEM is not about trying to encourage young women to take an interest in science – that interest is already there.

“I think the work now is to make sure that the scientific community is a place where women can actually thrive and that they are not going to be pushed out.”

The stories of three VIU alumni highlight the creativity and innovation that women are bringing to STEM fields and are an inspiration to young girls interested in pursuing careers in these areas. Read on to find out how each of these women is solving problems, answering questions and making the world a better place with their education.

Measuring Molecules: Larissa Richards

Larissa Richards is happily challenging the perception that all chemists wear white lab coats and mix colourful solutions in test tubes and beakers in a sterile laboratory.

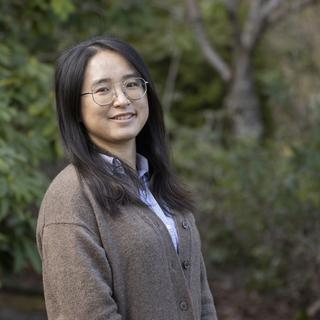

Richards is a PhD candidate in chemistry at the University of Victoria and is currently working on her research project in VIU’s Applied Environmental Research Laboratories (AERL) under the supervision of Dr. Erik Krogh, Co-Director of the lab.

Now in the final year of her PhD, Richards is working in the Mobile Mass Spectrometry Lab, a.k.a. the Mass Specmobile, which is driven around communities measuring trace-level contaminants to find the sources of different volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere.

“I spend most of my time in the mobile lab and then on the computer conducting data analysis, which is not what people think of when they think about chemists. We use advanced instrumentation to measure a chemical fingerprint of the air as we drive, and that chemical fingerprint changes depending on where we are,” explains Richards.

For example, if the Mass Specmobile drives by a gas station that is surrounded by trees, or through an area that has many different types of industry, the air might contain molecules from each of these sources. Richards is trying to de-convolute the chemical fingerprint to figure out where the molecules are coming from, and map those sources over space and time. Volatile organic compounds impact local air quality, and have both natural and human-made sources. The Mass Specmobile is a powerful tool for studying these molecules in our community.

There was a time when research wasn’t on Richards’s radar. Her post-secondary journey began in engineering physics, which she dropped about a year and a half into the program. When she came to VIU to complete her degree with the goal of becoming a high school math teacher, she decided teaching at the university level was where she wanted to be, but that meant getting a PhD.

“It’s more than just becoming a teacher. We need to train people who can solve problems and getting a science education helps with that.”

Richards says she ended up doing her PhD in chemistry because of the support and encouragement of the faculty at VIU, particularly Krogh, who exposed her to atmospheric chemistry and research.

“Sometimes you just need to take the right course with the right person and then it can spark your interest in something,” says Richards. “I really enjoyed environmental chemistry and Erik encouraged me to pursue that interest in graduate school.”

Taking Science to New Heights: Megan Willis

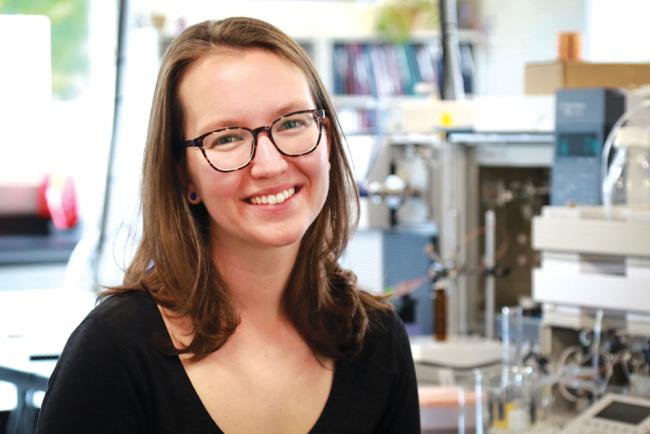

Megan Willis is part of an interdisciplinary group of environmental scientists studying atmospheric chemistry and how airborne particles affect the climate.

As a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) post-doctoral fellow at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab in California, she spends her days focusing on the molecular-level chemistry that drives aerosol properties in the atmosphere – a role she never saw herself in during her high school years “just because it was totally outside of my field of awareness.”

Her interest in environmental chemistry was sparked by courses and hands-on research at VIU. “I honed in on how we can use analytical chemistry to make measurements of the atmosphere and some of it just blew my mind,” she says.

Willis spent three summers working as a full-time research assistant in the AERL. She says having the opportunity to work in the lab gave her practical experiences and helped build her confidence.

“I didn’t know what it meant to do research and couldn’t see myself in a place like that,” says Willis. “Just being in a supportive environment, being able to make mistakes and try things was transformative.” Willis is also a founding member of the VIU public outreach group Awareness of Climate Change through Education and Research (ACER).

She completed her PhD at the University of Toronto in 2017.

Her work focused on atmospheric chemistry observations collected in the Canadian High Arctic, using a mass spectrometer in an airplane to hone in on the influence of sea ice loss on Arctic aerosol chemistry and clouds. While she isn’t flying around the Arctic any longer, she is continuing her research focusing on detailed mechanistic chemistry in the lab. “My goals at the moment are to continue doing research,” says Willis. “I really like working with other people in a mentoring type relationship, and working in a research-focused university would be ideal.”

Building Better Medical Equipment: Tori Koelewyn

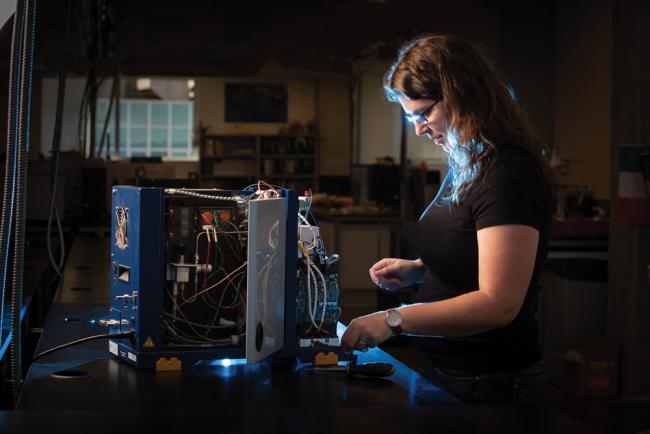

Tori Koelewyn has spent a great deal of the latter part of her engineering degree designing complex biomedical devices and equipment to help doctors help people.

“To maintain a certain level of happiness in my work life I need a job that helps people,” says the 24-year-old, who started her education in VIU’s Engineering transfer program. “I think biomedical engineering is the best place for me to do that.”

Koelewyn, who is from Vancouver Island, entered the VIU Engineering transfer program right out of high school. She initially thought she’d go into civil or electrical engineering; however, the University of British Columbia (UBC) introduced her to the broad spectrum of engineering careers available, including engineering physics, which she fell in love with.

She chose to specialize in orthopedic surgery and biomechanics after taking an anatomy elective.

“I was fascinated specifically by the way the body moves,” explains Koelewyn. “I would read papers on biomechanics and engineering technology development, and when I ate lunch with friends, I would watch people walk by and pay attention to how their body moved to make each step. It sort of took over my life.”

Koelewyn used the knowledge and skills she learned to work on several biomedical engineering projects while obtaining her degree. She redesigned a device used in guided dental implant surgery called a patient tracker for Navigate Surgical, which had limitations preventing doctors from using it in all situations and on all patients. The new “patient tracker” device took many attempts to perfect, but it worked.

For a school project at UBC with a colleague, she developed an inexpensive device that tracks movement data for patients’ pre- and post- knee or hip replacement surgery that allows doctors to intervene when the patient is exercising too much or not enough. During a semester abroad, Koelewyn also worked on a project to redesign an operation tool to save time in orthopaedic surgeries.

She graduated this spring with an engineering physics degree from UBC, specializing in biomechanical engineering.

“My goal is to end up in project-based work, specifically mechanical design, while keeping doors open for graduate studies. I love learning and with each project comes a whole new set of challenges in learning anatomy, physiology, technical requirements, brainstorming, and design. I thrive in this kind of environment.”

Sidebar: Careers in STEM

- $26-$69/hour: Starting wages for computer and information systems managers.

- $20-$67/hour: Starting wages for civil engineers.

- 95,000+: Engineering jobs are expected to be available by 2020 due to retiring employees.

Sources: engineerscanada.ca; workbc.ca; BC Labour Market Outlook (2018 edition)