Expert commentary with Dr. Stephen Davies, Director of the Canadian Letters and Images Project

Vancouver Island University History Professor Dr. Stephen Davies is founder of the Canadian Letters and Images Project, an online, digital archive of Canadian wartime letters and related materials. He started the project in 2000 to help his students understand the First and Second World Wars. Over the past 23 years, the website has grown to include more than 35,000 letters as well as images, diaries and other materials.

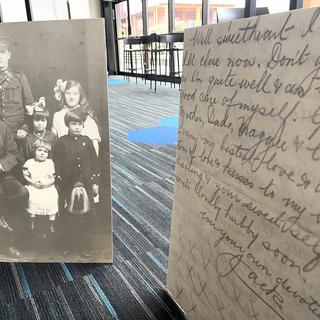

Through this project, people can learn about the wartime experience through the words and images of ordinary Canadians. The letters and photographs are sent to Davies by families across Canada to be scanned. Once they are part of the collection, he returns the originals to the family members.

We caught up with Davies to learn more about the project and its impact across Canada.

What made you decide to start this project?

I teach World War One history. For me, letters are one of the most important teaching tools in terms of understanding the war and the loss of war. When I started the project, there weren’t any Canadian materials online at that point. So, I started the project for my students, hoping to get a hundred or two hundred letters online that they could work with. And from there it just snowballed. People found out about it and wanted to contribute. The effort grew from a class project of a hundred letters to a national project of 35,000 letters now and it continues to grow.

The letters are a powerful teaching tool because they put a human face to war. When you are teaching about large battles, where you have 10,000 or 20,000 casualties, the numbers become so large that they become meaningless. When you can reduce that down to a single individual, a collection, and you can read about individuals like Lawrence Jodoin, who had a girlfriend, he had ambitions, he had a dog, he loved chocolate. You get a sense of the loss that one life entails. Then extrapolate that 20,000 times and you realize the richness of what we’ve lost.

The letters tell the story of war without a lens of interpretation. You’re seeing through the eyes and in the words of the participants without a historian telling you what they thought about it. You really get a sense of what they thought and what they went through.

Can you talk about some of the reactions to the materials that you’ve witnessed over the years?

The emotional side is really what comes through the letters. One of the most important experiences I’ve had in terms of the teaching experience was when I led field schools in Europe that visited the Western Front. They were each assigned a soldier from the Canadian Letters and Images Project. As part of the coursework, they wrote the biography of that soldier based on the letters and diaries in that collection. What I hadn’t told them, though, was that they would be presenting at the gravesite, at the memorial where the person had been laid to rest. Students were openly crying because they’re standing beside the grave of a person they’ve gotten to know. They know what they like and dislike, they know their sister’s name, they know everything about them. And there they are reading these letters and talking about the biography of the soldier next to their grave. That was a transformative moment for so many of the students. It was very, very powerful.

Can you share one or two soldier stories that have stood out for you?

There’s so many that stand out. I can share two that resonated.

We have a collection from a World War One soldier named Hart Leech. He wrote a letter to his mother in September of 1916 – what was known as a post-mortem letter. Post-mortem letters were written by the soldiers as their last letter. They would give them to their officers and if they were killed, the officer would mail them. If they survived the attack, the officer would give them back and then they would tear them up. In this last letter to his mother, what struck me was his stoic acceptance of his fate. The likelihood of him surviving was low and he knew that. He was telling his mother that, but also the letter was tinged with humour. He tells his mother that, if he gets killed, well, it would be while doing his “blooming job” and he “kicked out with his boots on.” That letter always stuck in my mind. He knew he was probably going to be killed and yet he’s got this sense of humour about it. And indeed, he was killed a few days later in the attack. The officer himself was also wounded, and the letter got lost in his effects. So, the final letter to the mother wasn’t delivered until 1928. Twelve years later, she finally got the last letter from her son.

This past summer we worked on a collection about Lawrence Jodoin from Calgary, who joined the Navy. He was 18 when he enlisted in 1943. He came to Esquimalt on Vancouver Island for initial training. And while he was only there for a short period, he met a young woman at a dance and they started to correspond. The evolution of the correspondence is very interesting. It evolves from “your friend” Lawrence to, “hope I can be more than your friend” to “love Lawrence.” You can see this relationship that develops. He was killed in July 1944 just after D-Day. I found it really, sad, really touching, this 18-year-old who never had the chance to grow up and have a real relationship. And his love interest kept these letters – we got the letters from her daughter so she had not thrown them away.

What are some of the most unique ways you’ve seen the Canadian Letters and Images Project used by individuals, schools or organizations?

Many schools incorporate the letters into their Remembrance Day ceremonies, reading the letters aloud. Some have put some of the letters to music. For example, there’s a musical. A professional musician in Stratford and the Stratford Symphony took a collection of letters from a couple from Stratford, Ontario, and they turned it into an opera based on the letters.

HomeEquity Bank took addresses from the letters in the project, where veterans had lived, and mailed out the letters to those houses. They made an interactive map as well so you can see who lived where based on the materials from the project.

True Patriot Love, which is a charity which looks after modern-day veterans, created paintings using artificial intelligence. The paintings were based on some of the letters from the project and were amazing visual interpretations of letters. It was interesting to see what the AI software came up with based on the content of the letters. These paintings were sold as part of their fundraising efforts.

So, we go from the usual scholarship uses, to the letters being turned into musicals and radio plays, to artificial intelligence. The project keeps turning up in non-conventional ways, I keep seeing the letters being used in a very creative manner.

How can people get involved?

If people want to support the continuation of the project, they can donate through the VIU Foundation, which is a tax-deductible donation. The project currently has no government or corporate support to keep it functioning. You can indicate that the donation is to go towards the Canadian Letters and Images Project.

I also encourage people to share their collections. We want to make sure that these stories are preserved, that they’re brought out of closets and attics and that Canadians are aware that what they have is very, very important. The project only borrows the materials for digitization and then they are returned to the families.

Finally, I urge people to go online and spend some time reading the letters on the website and reflecting on the experiences recounted by these soldiers. Search the Hart Leech collection. Read his last letter to his mother and think about what that means.

What are you most proud of achieving thorugh the Canadian Letters and Images Project?

It’s the project’s ability to bridge the university and the wider community. Too often academics end up writing for other academics. They will publish articles and books that are largely read by other academics, other historians. In the case of the Canadian Letters and Images Project, the materials are being used by professional historians. But these materials are also being used by Grade 5 students. There are very few historians who can say that they’ve created something that can be used both by the leading historians of the day, and by Grade 5 students, and everyone can get something from the materials.